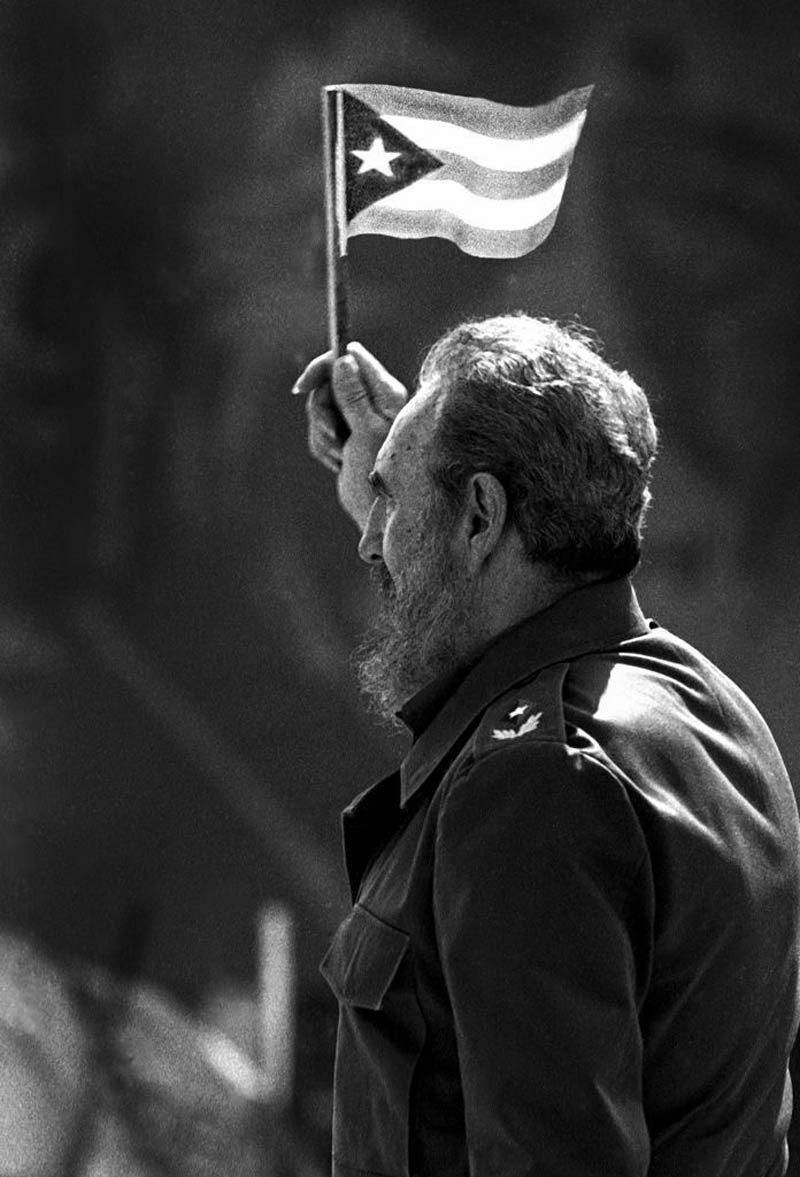

Fidel Castro, The Last Knight?

- Written by Cubadebate

- Published in Photo story

- Hits: 3798

Photo: Ismael Francisco/ Cubadebate.

Photo: Ismael Francisco/ Cubadebate.

We entered the dark and uncertain tunnel of the 90s of the last century and only spoke of the ineluctable destiny of Cuba that, according to the theorists of the end of History, would not survive the socialist collapse of the USSR and Eastern Europe.

Chroniclers interested in deciphering the mystery of island resistance came from everywhere, the most serious ones; the rest one only wanted photos of the broken buildings and the material poverty that was advancing, scaring them more than any of us, although the story was spiced up by Creole testimonies of the impact of the scarcities.

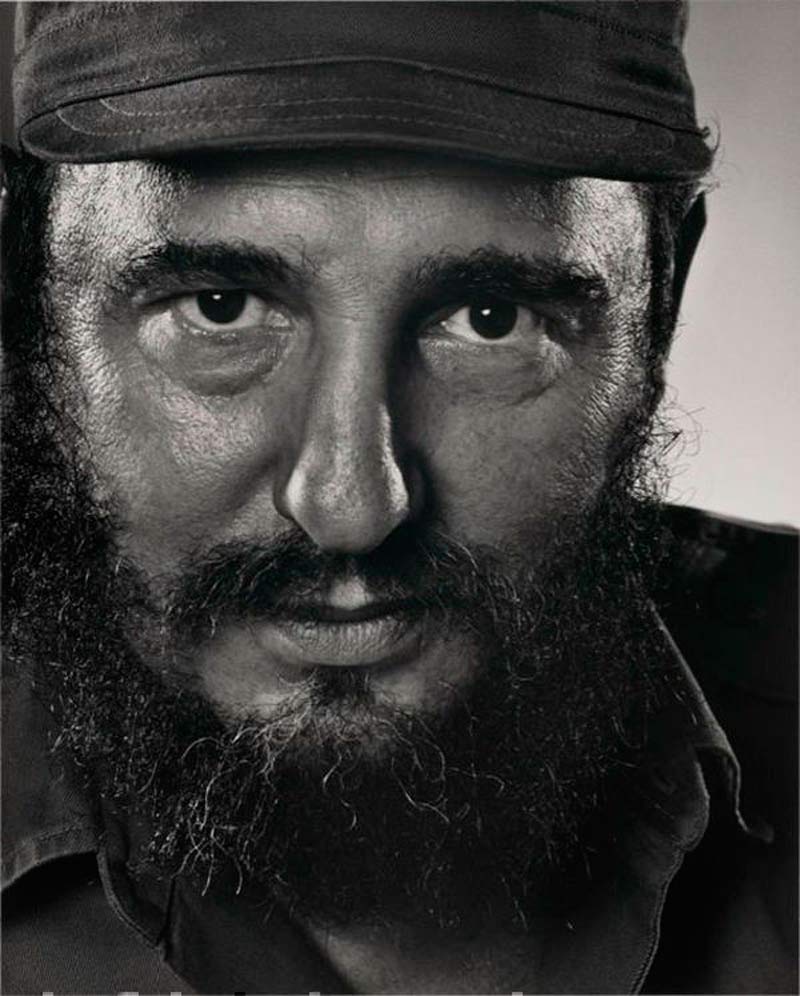

In Cacahual, La Habana (1961). Photo: Liborio Noval.

In Cacahual, La Habana (1961). Photo: Liborio Noval.

Two years after the beginning of the decade, the Torricelli Law was signed and the UN General Assembly began to approve the condemnations of the blockade with its non-binding resolutions, which remain ineffective as far as we know: the United States does not care what other governments agree to.

It was in those years that I read a chronicle whose title I do not forget: "Fidel Castro: The Last Knight of the Twentieth Century." This is how the author called the Leader of the Cuban Revolution, appreciating his exquisite manners and the way he faced and responded to his greatest critics (who were almost all the politicians of the time), without ever falling into vulgarities or slight disqualifications.

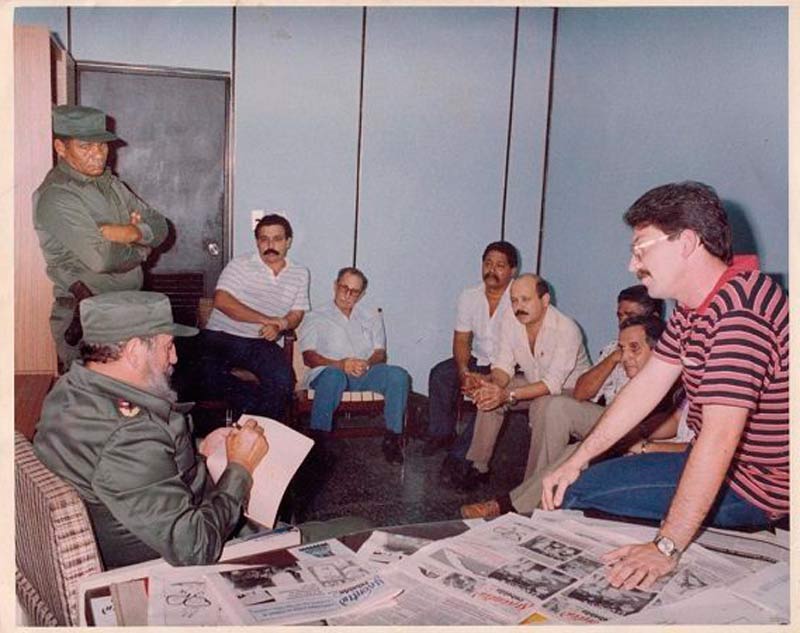

One night in September 1990 he visited the Juventud Rebelde newsroom to explain to us that there would be a strong cut in the printed press. Paper became enormously expensive and there were unquestionable priorities: milk, for example. He did not send emissaries or letterhead. He sat down to explain what was coming: in our case the transit from daily to weekly newspaper with half the pages and smaller runs.

Fidel in a visit to Juventud Rebelde in the 90's. Photo: Archivo JR.

Fidel in a visit to Juventud Rebelde in the 90's. Photo: Archivo JR.

I don't remember him upset or sad. He recommended sending the excess staff to the audiovisual media and never neglecting them. They would continue to get paid by JR because one day, not too far away, they would return to the central newsroom to resume the dynamics of the newspaper.

"If we resist five years, we get out. Five years ..." I remember him saying. The newspaper must still keep the manila envelope in which he drew project sketches for the Metropolitan Park and other programs that encouraged him to think with optimism that the rest lacked.

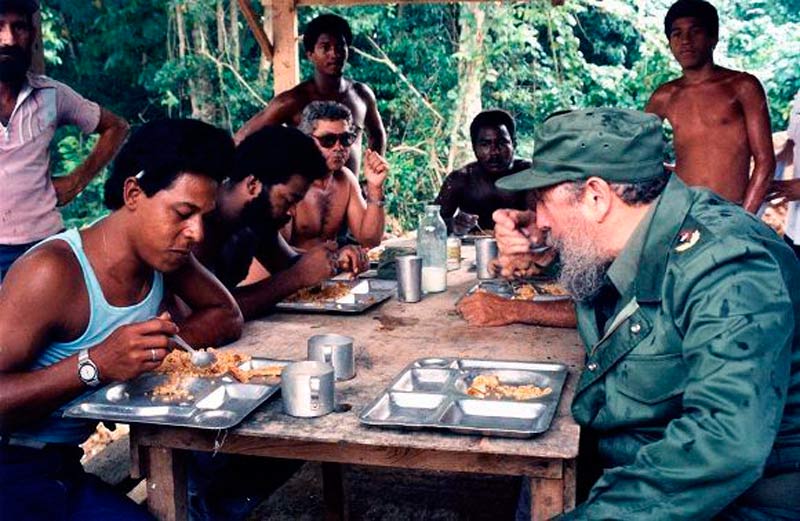

There are hundreds of photos of his intense activity during those years. There were days of three or more speeches or interventions by him, explaining and encouraging. He became a regular visitor to the Blas Roca, the agricultural camps with mobilized people, the pedraplenes, the centers of the scientific pole, the hotels under construction for international tourism. Nothing is more graphic than an image of him sharing lunch on a tray with a group of mobilized people in the then very popular Paraíso (camp) of the UJC.

He toured neighborhoods, workplaces, and construction sites inquiring and responding. The whole of Cuba was his troop. And with his troops he discussed the most dissimilar topics, always including a question about what we were reading.

With workers of the Blas Roca contingent, November 6, 1988. Photo: Estudios Revolución / Sitio Fidel Soldado de las Ideas.

With workers of the Blas Roca contingent, November 6, 1988. Photo: Estudios Revolución / Sitio Fidel Soldado de las Ideas.

He distinguished women, did not accept professional teasing, and immediately put a stop to any attempt to publicly undermine the work of someone absent. And he opened space in his conversations to a bricklayer as well as to a famous intellectual or artist, with special care for women, the elderly and children.

Yes, Fidel Castro Ruz was a real gentleman. Knight in the most respectable sense of the term, the truth ahead. And he knew how to say it in the least harsh way possible, unless he was referring to the historical adversary of the Cuban nation. Those he accused relentlessly and without fear. In the most objectionable words and in the harshest terms. In the style of that fence in the middle of the Havana seawall and where a Cuban tells the "imperialist gentlemen (that) we are absolutely not afraid."

He was outraged by lies and vanity, cowardice and vassalage. All the messengers of the empire who tried to drag Cuba into the neoliberal wave that would devastate Latin America in the 90s, deepening social inequality, are well aware of this.

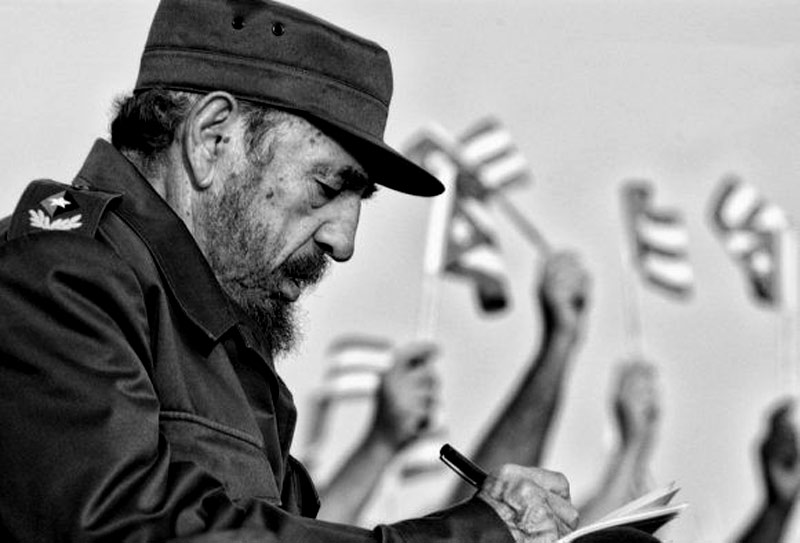

"Mayo 1st parade in La Habana" (2001). Photo: Liborio Noval.

"Mayo 1st parade in La Habana" (2001). Photo: Liborio Noval.

After attending two Ibero-American Summits as a journalist in which the protagonist was Fidel (Madrid 92 and Salvador de Bahía 93), I better understood why that European journalist who visited Cuba at that time described Fidel as the last gentleman.

Several heads of state and government of the region acted as simple "runners" of the old metropolis and the new empire, giving recommendations to Cuba. Fidel, without fanfare, but firmly, spoke to them of courage, commitment, and revolutionary ethics. They couldn't understand it.

The 20th century has passed, we are entering the 21st, and almost all of Fidel's forecasts and warnings have been fulfilled or are in the process of being fulfilled. He left this world politically and morally undefeated, but he will not be the last gentleman, as long as his art of doing politics is appreciated and assumed as one of Fidel's fundamental legacies.